💚🤍❤️ Cari lettori buongiorno!

At Liguria Letters, we are passionate about exploring life in Liguria, its culture, history, and stories. Today, we highlight La Belle Époque (1871-1914). Our journey will take us from Genova and Alassio in Liguria to various locations, including Pachino in Sicily, Beinette in Piemonte, Garda in Veneto, the French Riviera, Spain, and Morocco.

Join us as we uncover the life story of Alessandra di Rudini (1876-1931)!

Author Fabio Gaggia, who graduated in Literature and Philosophy from the University of Padua, in his richly documented biography Alessandra di Rudinì, Una nobildonna della Belle Époque (2013), reconstructs her remarkable life. In his introduction, he tells us that Alessandra led a complex and dramatic life, not easy to summarise in a book (let alone in one newsletter, I’m thinking).

With his book in hand, let’s get to know this nobildonna, this noble lady, as indicated by the title. Alessandra di Rudini was born in 1876 into an extremely wealthy family as Maria Antonietta Livia Starabba, daughter of Antonio Starabba (1839-1908), who in 1897 obtained the title Marchese de Rudini, and Maria de Barral de Montauvrard (1845-1896), daughter of Charles de Barral de Montauvrard, an officer in the French army, and Alessandrina Nikiforoff, a descendant of Russian nobility. Alessandra had two brothers, Francesco and Carlo Emanuele.

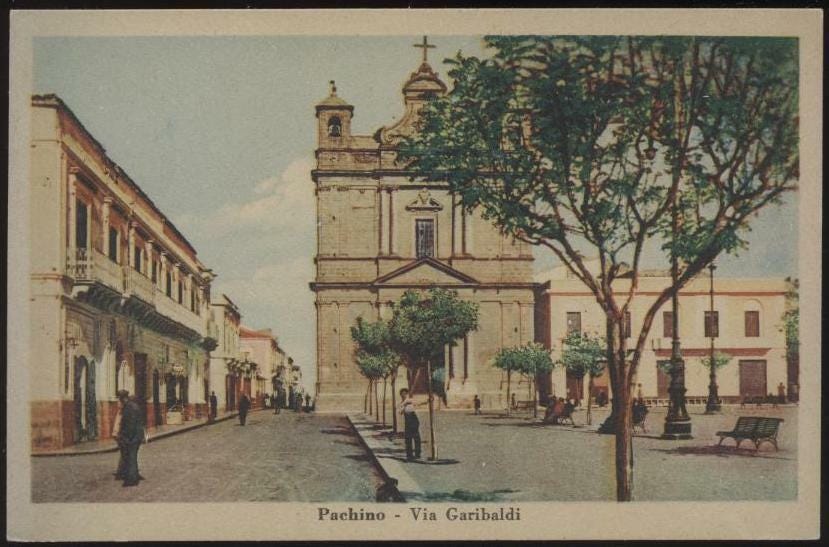

Alessandra’s father was a landlord who governed his lands in Pachino, Sicily, with a liberal approach. During the harvest season, the family was welcomed by local nobility and farmers, who, following tradition, offered them bread and salt on a silver tray, along with the keys to the gates of the village (p.11, note 2). In 1864, he became the mayor of Palermo, marking the beginning of his career as a socially engaged politician. He was elected Prime Minister of Italy twice, in 1891 and 1896.

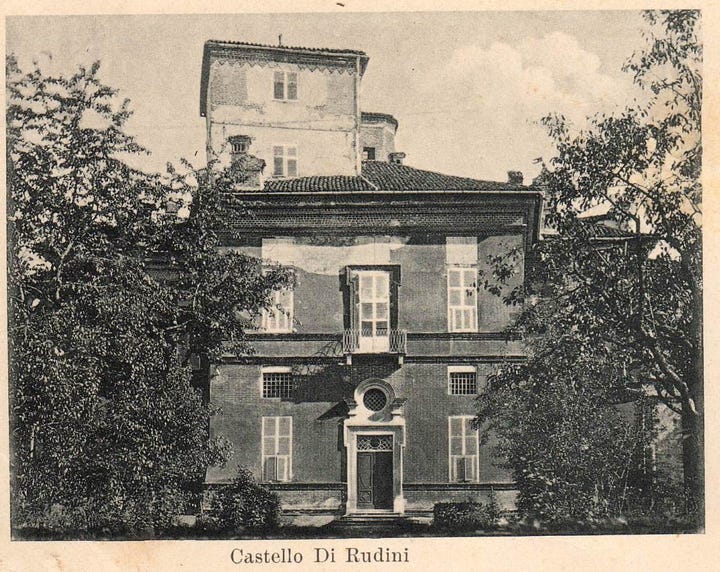

Her mother’s family owned a castle-like mansion in Beinette, in the province of Cuneo, in Piemonte, located northwest of Savona. Although this former villa still stands, the residents and the municipality of Beinette would like to see the castello, as they call the house, restored and given a new cultural purpose. Unfortunately, this has not yet occurred, and the building is increasingly becoming a ruin, overtaken by nature. The illustrations below show the house in the days when Alessandrina, as her Russian grandmother affectionately called her, spent her childhood in this family home, contrasting with its current status.

Fabio Gaggia notes that Alessandra was described early on as skittish, rebellious, restless, and full of contrasts (p. 35). We don't have much information about her early school years. Like many girls from affluent backgrounds, she was likely homeschooled by a governess, whose name we do know: la signora Sampò (p. 35). For further education, she attended two renowned, internationally-oriented institutions for students from wealthy families: the Sacro Cuore della Santissima Trinità dei Monti in Rome and the Santissima Annunziata di Poggio Imperiale in Florence. At the institute in Rome, Alessandra struggled to adapt. She was: caught pouring ink into the holy water, climbing trees, and wandering the halls at night (p. 36). Due to this unruly behaviour, she was sent home. However, at the second institute in Florence, she applied herself seriously, studying Latin and Greek and mastering four additional languages: French, English, German, and Spanish.

At the age of seventeen, after four years of strict internment under the care of Catholic nuns, Alessandra had transformed into a beautiful, elegant, and well-educated young lady. She was ready for marriage, but her non-conformist attitude clashed with the prevailing nineteenth-century patriarchal conventions for women. For example, Alessandra engaged in philosophical and political discussions with guests at her father's house, enjoyed riding horses and galloping through the countryside, and became one of the first women to drive an automobile.

In 1895, despite her father’s suggestion to marry a suitable partner from the Russian nobility, Alessandra chose to marry the Marquis Marcello Carlotti di Garda (1866-1900). The couple settled in Villa Carlotta, a grand estate in Scaveaghe, between Garda and San Vigilio in Veneto. Alessandra wrote about this stunning place, surrounded by beautiful vegetation and offering panoramic views of the lake:

Il tempo qui è magnifico, rifrescato leggermente da qualche piccola pioggia. Il lago è nei suoi giorni di meravigliosa bellezza, la natura ci dona le sue più belle, le più rare sinfonie.

The weather here is magnificent, lightly refreshed by a bit of rain. The lake is in its days of marvellous beauty, nature gives us its most beautiful, rarest symphonies. (p.13, note 11).

The property is currently privately owned and is known as Villa Carlotta Canossa.

In 1896, they welcomed their first son, Antonio, and their second son, Andrea, in 1897. While their marriage was socially successful, Alessandra and Marcello had very different personalities, so it's uncertain if they found true happiness together.

The couple lived when interest in the Orient and the romantic idea of travelling to distant lands began to thrive. Europeans were increasingly captivated by Oriental cultures, beliefs, and lifestyles. Gaggia notes that newspapers such as L'Arena from Verona reported on various topics, including Muslims making pilgrimages to Mecca, the history of coffee, and boat trips along the coasts of Morocco, the Azores, and Madeira (pp. 96-97, note 2).

Not only did male European explorers and missionaries undertake these journeys, but several women also played a significant role. Two notable examples of female pioneers are Dutch explorer Alexandrine Tinne (1835-1869) and Swiss adventurer Isabelle Eberhardt (1877-1904). See the illustrations below:

Alessandra and Marcello shared a dream of embarking on such a journey. Tragically, their marriage was cut short when Marcello, suffering from tuberculosis, passed away in 1900, despite the efforts of the best specialists in Italy and France. This left Alessandra a widow at the young age of twenty-four.

The travel stories deeply impressed Alessandra. After the required lutto, the mourning period for her late husband, and now, as an independent and impressively wealthy widow, she decided it was time for a break. Leaving her children in private care, she set off for Nice and the French Riviera around January-February 1901. From there, she continued her journey to Pau, not far from Lourdes, and then to San Sebastian. In San Sebastian, she reunited with a British friend from her youth, who was just as affluent as Alessandra and owned a large ship. The two women decided to sail to Rabat and then to Casablanca to embark on an adventurous exploration of the desert between Morocco and Algeria (pp.97-101).

The reasons behind Alessandra's decision to embark on this adventure remain a matter of speculation. It's likely that she was influenced by the romanticised image of the Orient prevalent at the time. Was she seeking to process her emotions following Marcello's death, which came shortly after her mother's death? Or was she looking for new religious experiences, as some sources suggest? Ultimately, only Alessandra truly knows her motivations.

In this remote area inaccessible to Europeans, especially to women, I envision the two lady-friends, their heads filled with romantic ideas about the Orient, bravely travelling in a convoy accompanied by Arab guides, just like Alexandrine Tinne had done before them. According to research by Fabio Gaggia, we do not know the exact itinerary Alessandra took in Morocco. It certainly was not just a viagetto, a little trip in those days. While staying in luxurious Tangiers, sipping cocktails and playing lawn tennis, as some European visitors did, is one thing, crossing the desert is an entirely different matter. That venture was fraught with danger, including murderous attacks on women explorers, along with a precarious political situation to consider. Overall, it was not a safe environment for travel (pp.97-108).

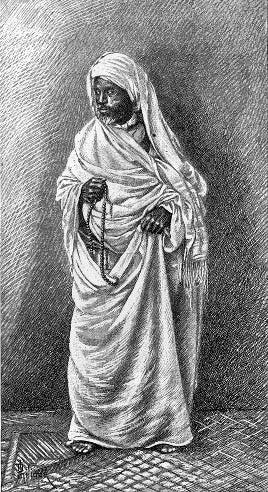

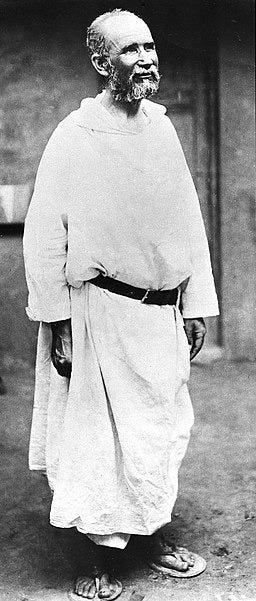

Sources indicate that Alessandra crossed the desert while wearing trousers, a bold choice for women at that time, which was neither accepted nor appreciated by men. Other accounts suggest that she wore a burnous, a flowing cloak with a hood typical of Arab attire (p.110, note 17). There is also a legend about a Marabout, which refers to Muslim religious teachers in this part of North Africa, known for their magic and prophecies. Alessandra is said to have encountered a two-hundred-year-old Agurram (another term for Marabout) who spoke French and was knowledgeable about the Gospel (p. 101, note 21). This mystic foretold her transition from luxury to poverty, from love to loneliness, ultimately leading her to live near a mountain.

Other stories of her journey describe how Alessandra met Count Charles de Foucauld (1858-1916), who, like her, was a descendant of a wealthy family. As a geographer and cavalry officer in the French army, he had already explored Morocco from 1883 to 1884. He documented and mapped the landscape in a travel memoir, for which he received a gold medal from the Société de Géographie de Paris in 1888 (p. 101, notes 18-21).

In the same year Alessandra arrived in 1901, he returned to North Africa. He chose to live as a hermit, embracing a spiritual life in the desert and dedicating himself to translating the word of God into Arabic. After his calling to the priesthood, he changed his name to Brother Charles of Jesus and sought to improve the situation of the Berbers. He believed that, in this Islamic country, this could only be achieved by spreading the Christian faith. Tragically, he was brutally murdered in 1916. In 2005, Charles Foucauld was canonised by Pope Benedict XVI (Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger).

In June 1901, Alessandra returned safely to her villa in Garda. The prophecy of the Marabout and her encounter with de Foucauld had a profound impact on her. As a result, she became more introspective, reflecting on various religions and reading philosophical works in her library. In the aristocratic Salons, she shared her experiences from Morocco.

In 1903, she crossed paths with a new figure in her life: Gabriele D'Annunzio, an author, poet, fighter pilot, and politician (1863-1938). She later met him again in Milan at a concert featuring the world-famous opera diva, soprano Gemma Bellincioni (1864-1950), and again at her brother Carlo’s wedding.

D'Annunzio, known for being a womaniser and a big spender, was officially married to Maria Hardouin di Gallese, Principessa di Montenevoso (1864-1954). When he met Alessandra, he was in a relationship with actress Eleonora Duse (1858-1924). However, he left his beloved of decades and began writing numerous amorous letters to Alessandra, calling her his Niké, after the Greek goddess of victory.

Alessandra's move to La Capponcina, D'Annunzio’s home near Florence, marked the beginning of a passionate and turbulent liaison criticised by European aristocracy. During this time, Alessandra squandered her family’s capital on an excessively luxurious lifestyle (pp.123-163).

Alessandra falls ill and requires two surgeries, from which she barely recovers. This becomes a turning point; she reflects on her lifestyle and returns to Garda in 1907. Eventually, D'Annunzio leaves her. Moving on and healing from the broken relationship proves to be quite challenging for her. Between 1907 and 1911, she frequently attempts to reconnect with her former lover.

Still searching for spiritual meaning, Alessandra decides to go on a pilgrimage to Lourdes. There, witnessing the numerous sick and desperate people, she finds faith. After taking her sons on holiday to Genova and Alassio, she chooses to join a monastery, the Carmel of Paray-le-Monial in France. She begins her secluded life as Sister Mary of Jesus.

What ultimately drove her to make this significant decision, which likely affected her children, remains a matter of speculation. Perhaps she had grown weary of the extravagant society she was part of, tired of the inner turmoil she was experiencing, or sought the safety and peace offered within the walls of a cloistered monastery. (pp. 307-310).

She became an exemplary nun and, later, as Mother Superior, founded three additional monasteries: one in Valenciennes, another at the Carmel of Montmartre, and the last at Le Reposoir in Haute-Savoie. Alexandra passed away in 1931.

In addition to the book by Gaggia and various biographies of Alessandra di Rudini written by other authors, there is also a unique book titled Mère Marie de Jésus, fondatrice et prieure du Carmel de Paray-le-Monial (1853-1917), author unknown, published by the Monastère de la Sainte Trinité in 1921. This book details Alessandra’s early years as a novice, her spiritual journey, exemplary behaviour and ideas, and highlights her significant role as Mother Superior for the Carmelite order. Please see the link below for more information.

💚🤍❤️ Did you enjoy this newsletter? Let us know, like or subscribe, it’s free!

Alla prossima!

Sources:

Fabio Gaggia, Alessandra di Rudini, Una nobildonna della Belle Époque, Cierre edizioni, Verona, 2013.

Citation taken from G. Moncalvo, Alessandra di Rudini dall’amore per D’Anunzio al carmelo, Milano 1994, p.344. See Fabio Gaggia, Alessandra di Rudinì, Una nobildonna della Belle Époque, note 11, p.13. The translation is mine.

Lucy Napoli Priario, Tre Abiti Bianchi per Alessandra, Mondadori edizioni, Milano, 1955.

Mère Marie de Jésus, fondatrice et prieure du Carmel de Parag-le Monial