💚🤍❤️ Discover Verona through the eyes of an author with us!

Liguria Letters travelling in Italy.

💚🤍❤️ Cari lettori, Buongiorno!

Liguria Letters travelling in Italy!

Today, we have an inspiring story about our trip to Verona, a beautiful city located in Veneto, that is easy to reach from Genova by car, via Piacenza and Brescia, or by train via Milano.

Verona has enchanted artists and authors throughout history. Writers such as Dante, Goethe, and Dickens have expressed their fascination with this city on the Adige. It served as the stage for the famous love story of Romeo and Juliet, as depicted in William Shakespeare's play. The Arena is renowned for its yearly Opera Festival.

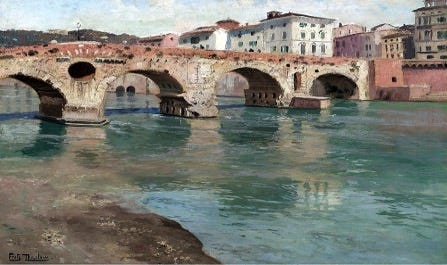

The Norwegian Impressionist painter Frits Thaulow created the painting featured in the illustration below. It portrays the Ponte di Pietra in Verona, providing a glimpse of Verona’s beauty.

In 1983, one of my favourite Italian authors Dacia Maraini (Fiesole, 1936), known for her influential contemporary feminist literature, travelled to Verona in search of real-life stories to inspire a new novel. While there, she stumbled upon a newspaper article from 1900 detailing the murder of a young woman called Isolina Canuti. Captivated by the story, she took it upon herself to uncover the truth behind this article: she interviewd descendants of the Canuti family, collected newspaper articles, photos, and letters from 1900, and reviewed witness statements and trial reports revealing a negative image of the girl.

Based on this true story she wrote a historical novel: Isolina (Milano Rizzoli, 1985), translated into several languages, including English, that sent shockwaves through the country when it was first published.

The Story:

The novel is set in Verona in 1900, a patriarchal society where women are subordinate to men. Verona is also a garrison town where the elite and the army are in charge. Officers dominate the streets and contribute to the city's prestige.

In that same year, the body parts of a young woman cut to pieces and packed in burlap sacks were found by two washerwomen on the banks of the river Adige. Later, soldiers find other parts of her body, a miller finds a piece of her skirt, and playing boys get the fright of their lives when they find the head with a braid of hair still attached.

It turns out to be Isolina Canuti, nineteen years old and a few months pregnant by her lieutenant lover when she was murdered. She had refused to have an abortion and was killed by him and other army officers who wanted to protect their reputations. These men were tracked down but, after a legal trial, were never convicted.

Intrigued by Dacia Maraini's thorough investigation into this femminicidio as the murder of a woman is called in Italian, a phenomenon sadly still actual, and not only in Italy, I wanted to delve deeper into the story. With the book in hand, we discovered unique sights of Verona that are very interesting for you!

Join us on our literary city walk and discover Verona through the eyes of an author.

💚🤍❤️ In the footsteps of Italian author Dacia Maraini

As the evening begins, we arrive in the lively city of Verona. Our agriturismo Corte SanMattia, located in the hills, provides a peaceful escape from the bustling city centre and offers a stunning view of the elegant city and the Adige river. Ochre-coloured houses and green cypresses welcome us, creating a picturesque scene. Dusk descends over the Castelvecchio, the Piazza delle Erbe, and the Torre dei Lamberti, casting a magical veil over the city.

In the morning, we take the little circulator bus that drives from the hills towards the centre of Verona, where we get off at the Ponte Garibaldi, the bridge namend after nationalist Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882). As I stand here, I can see the river peacefully winding its way and then flowing more vigorously, just as Dacia Maraini depicts this view in her book.

To my left, two staircases lead to a broader area on the shore. It seems likely that this was one of the spots where the washerwomen worked in 1900.

As we continue our tour towards the centre, we arrive at the Corso Cavour, one of the busiest streets in the city, named after Camillo Benso di Cavour (1810-1861), the first Prime Minister of a unified Italy. Here Dacia Maraini stayed at the hotel Cavour in the Vicolo Chiodo, the Chiodo alley. She describes her tiny hotelroom overlooking a rooftop and the sound of pigeons bickering. In her footsteps we find this alley; the first thing one notices is a fierce cooing of pigeons! At the end of the narrow street we see the hotel, its name marked in tube letters.

Inside a friendly, somewhat older lady behind the reception. I tell her I'm researching Dacia Maraini. "Ah, la signora Maraini? Ma certo!" she replies, "I met her many years ago when she stayed with us."Would I like to see the room where the author stayed”? The lady precedes me on a narrow staircase, and suddenly, there I am, standing in a room, that is exactly as Dacia Maraini described it.

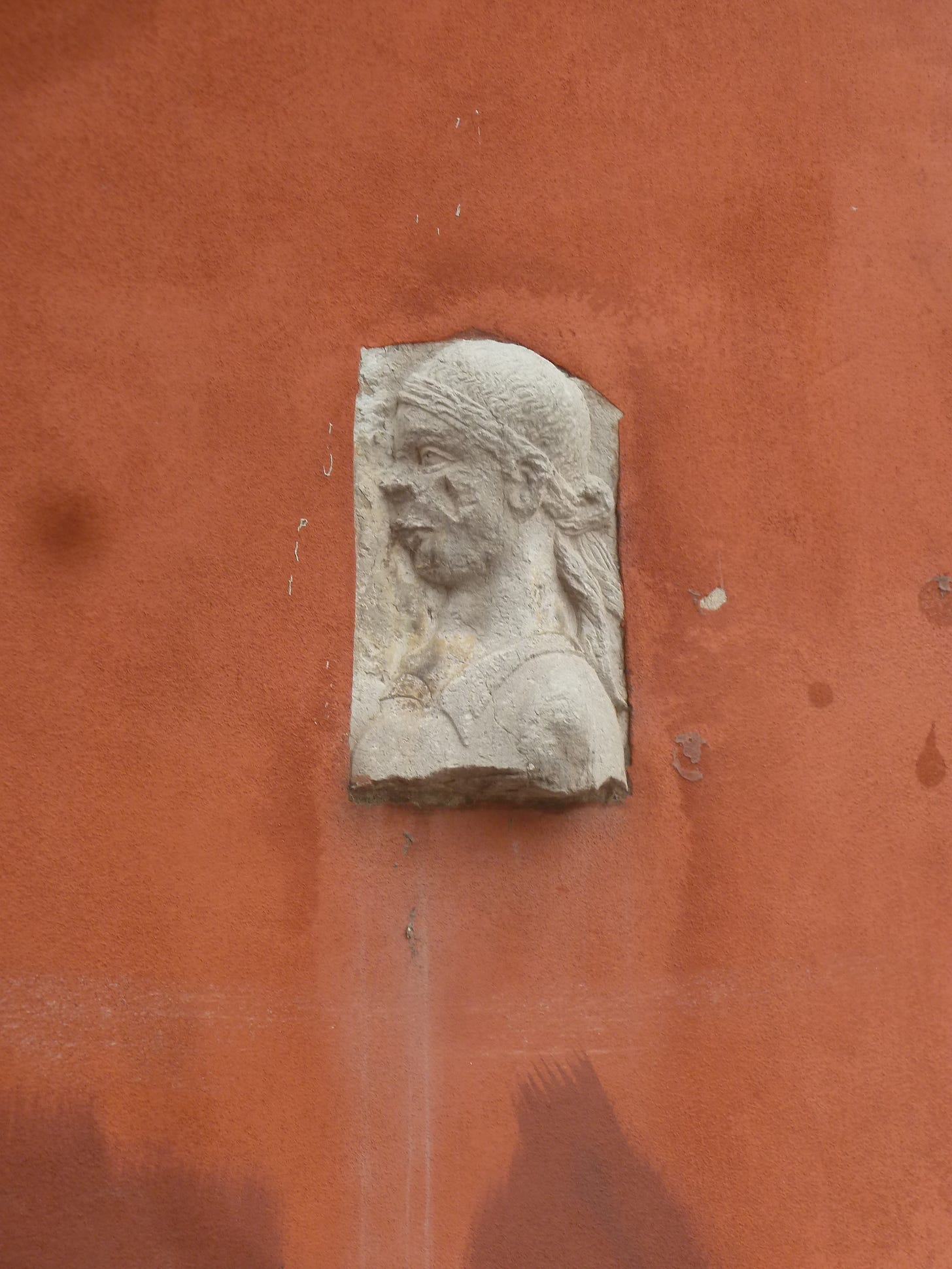

In this little backstreet there should also be a sculpture in relief with the portrait of a young woman in which, according to Dacia Maraini, people would like to see the face of Isolina. And indeed, there, where the Vicolo Chiodo crosses Corso Cavour, we find this little sculpture of Isolina on a bright red painted wall and for a moment, it seems as if she is looking at us...

In search of documents from 1900, Dacia Maraini visits the Archivio del Tribunale, the Legal Archive, and the Biblioteca Comunale, the Municipal Library. When she asks for the old court documents of the Canuti case and the testimonies' reports, they seem to be gone. "They were probably thrown away with other files" according to a janitor. It does not seem coincidental to the author, who eventually, after ongoing research does succeed in finding the court documents she needs.

From the Biblioteca Comunale, we walk towards the Castelvecchio, just like Dacia Maraini has done. We pass the Collegio delle Pericolanti, a two-story building with high windows. Its official name is Istituto San Silvestro, and the Sisters of Maria Bambina lead it. From 1200 to 1600, I read, it was a Benedictine convent, then the Penitenti, a group of lay sisters, took it over and then it became the Collegio delle Pericolanti, a re-education institute for girls who were in pericolo, in danger, because they were starving or of losing their virginity. Hence, the name Pericolanti can be translated as those who are at risk. According to Dacia Maraini, this was the boarding school where Isolina went as a little girl after her mother's death and walked around in the monastery garden.

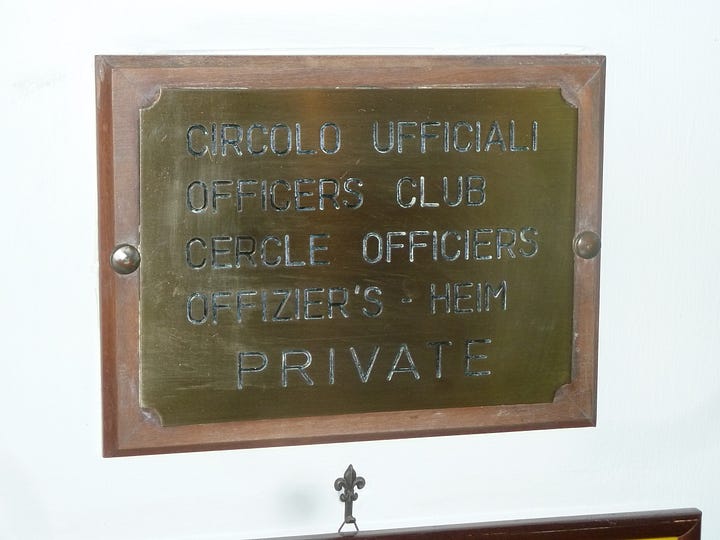

When we arrive at the Castelvecchio, we also find the Circolo Ufficiali, the private army officers club mentioned in the book. The castle, the drawbridge with chains and the chic interior of the club are precisely as described.

The author's quest, and ours too, ends at the Cimitero monumentale di Verona, the monumental cemetery of Verona. It is an awe-inspiring, unique place with a serene atmosphere. Large tombs of Verona's wealthy families, protected by marble angels, are interspersed with hundreds of white tombstones. There is an abundance of greenery and a nice breeze. Here, Maraini has searched for the tomb of Isolina and comes to the sad discovery that there is no stone or cross to be found in her memory. Her remains were probably buried together with those of others who did not get a grave in the Fossa comune, the public grave. Where can this be found? Is it still standing after all these years? There should also be a grave of the Spinelli family here, in which Nerina Spinelli, Isolina's mother, is said to be buried.

A little further on, gravediggers are working, so I decide to ask them. They are friendly and helpful and refer me to a small office where the graves are registered. When Dacia Maraini was in this building, she had to work through bookshelves with data from the last ninety years, but today, fortunately, all registrations have been digitised. According to their information, there is one grave in Spinelli's name where a Canuti is also said to rest: that combination is remarkable and makes us want to look for it. We find the Giovanni Spinelli and family grave located in the shadow of an arcade. Is this the tombstone of the Spinelli's that Dacia claims to find in the book? Are the mother of Isolina and some other family members buried here, too?

Under a scorching sun, we walk on a dusty gravel path with two adjacent rows of rectangular white tombstones. Maraini describes how the deceased follow you with their gazes from behind oval portraits on their tombstones. It's a strange feeling.

From this place, we can see a Pantheon containing the Chiesa del Santissimo Redentore, the Church of the Most Holy Redeemer, where an ampoule of Christ's blood is kept. According to the website of the Cimitero monumentale di Verona, the inscription Piis Lacrimis, Pious Tears, indicates the purpose of this sacred place among the tombs: to alleviate the grief of those who mourn their loved ones there.

We finally find the Fossa comune, where, according to Dacia Maraini, Isolina is buried. No marble tombstone with a portrait here, no flowers, there is a large grey round stone and an upright tablet that reads: ossario, ossuary.

Dacia Maraini's novel Isolina demonstrates how in 1900 in Verona the honour of the army was considered more important than the life of a young woman. Biased conservative judges and lawyers influenced witnesses, newspapers depicted a negative image of the girl.

Dacia Maraini portrays Isolina positively as a vivacious, and a little naive, young girl hoping to find some happiness. Seeking justice for Isolina, she has given her a voice.

It’s a moving moment to stand here, how could it not be? We leave flowers as a tribute to the young woman whom we can commemorate thanks to Dacia Maraini's efforts and leave the cemetery.

Sources:

Dacia Maraini, Isolina, Milano Rizzoli (1° ed. 1985) 2008.